Airbnb has a pricing strategy problem on extended stays (28+ nights), which make up to 25% of the nights it sells each quarter. The reason for this disconnect is that its service fees are too high compared to the value it brings as an intermediary to hosts and guests on these longer stays.

That may impact its ability to capture $210bn in long-term stays as stated in its IPO prospectus ($48bn in the serviced apartment/corporate housing segment and $162bn or 10% of traditional real estate rentals).

Airbnb has once again reported that a substantial part of its bookings come from extended-stay guests (those staying 28 nights or more). In market updates since Q3 2020, the total number of room nights booked as extended stays has averaged between 15.5-16m each quarter, representing 19-24% of total nights booked on the platform (or the equivalent of nearly 176,000 listings occupied full time). And in certain markets, the figure has been as high as 60% (our own data would support this, as we’re running at 75%).

13. So basically, people aren’t just traveling on Airbnb, they’re now living on Airbnb

— Brian Chesky (@bchesky) November 9, 2021

Back in late May, a headline from The Verge caught our attention: ‘Airbnb’s CEO thinks the platform can replace your landlord’. In the article, Airbnb’s CEO Brian Chesky said that deposits, long-term leases, and proof of income are outdated.

And we totally agree with this.

In fact, this is the foundation of our company’s thesis: residential real estate (especially apartment living) isn’t aligned to pillars of the 21st-century economy such as flexibility, convenience, and asset-light lifestyles. But that’s a story for another day…

That headline from The Verge has been bugging us for six months now, so it’s time for me to get it off our chest…

Let’s be clear on two things:

In this article, we’ll dive deeper into our rationale, based on our experiences running Lodgeur, where 75% of our room nights are rented by extended-stay guests.

Airbnb makes money primarily by charging a service fee to hosts and guests. This fee is predominantly paid by the guest, adding on average 14.2% to their cost, and 3% by the host (in a few markets, only the host pays the fee, and in others, they can elect to pay the whole fee).

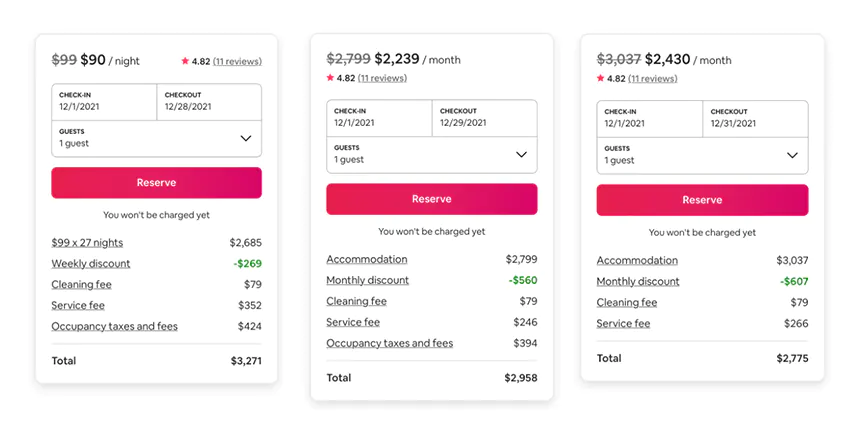

From analysis on our own listings, the average guest service fee is a smidge above 14.1%, but drops by a quarter if you book stays of 28 nights or more, to 10.6% or so. In other words, Airbnb can expect to receive 17.1% of the rent and fees charged by the host on short stays and 13.6% on extended stays. The guest may also pay local occupancy taxes, depending on the market and length of stay.

28 nights is also the magic number at which monthly pricing discounts (if offered by hosts) kick in. But a word of advice – if you see ‘Occupancy taxes and fees’ listed, these are often waived at the 30-night mark (depending on the local county, city, and state – we collect three sets of taxes in Houston). Unfortunately Airbnb’s system doesn’t flag this to guests, but we let them know manually. In fact, booking a stay of 30 nights with us is actually 15% cheaper than booking 27 nights once you add up the monthly discount, the service fee discount, and the occupancy tax waiver.

On the stay of 30 nights then, the guest will have paid $2,775 and Airbnb collects $341 between the host and the guest, which is equivalent to 13.6% of the actual cost charged by the host of $2,509 (of which it receives $2,434)

Pricing is probably our founder’s favorite ‘P’ of the traditional 4Ps marketing framework because it is so often overlooked. He loved it so much that his master’s thesis at the University of Cambridge focused on consumers’ marginal willingness to pay in short-term rentals. His research showed that while Airbnb provides value by making it easier for guests to find a place to stay and for hosts to attract these guests, the key value it sells to each side is trust.

That’s because using a marketplace platform such as Airbnb involves asymmetric information and risks, made worse by the presence of non-accredited individuals and companies (versus hotels). Adverse selection (famously described as the ‘lemons’ problem when buying a used car by Nobel prize-winning economist George Akerlof) arises when information asymmetries arise in a market. This is made worse in markets where consumers cannot inspect the quality of a service/product prior to purchase.

For experiential products such as booking accommodation, there is a high cost of failure. You can return a faulty product, but you can’t return a bad experience. The risk stretches beyond poor quality accommodation, with crime and a risk to personal safety in extreme cases.

That’s why Airbnb goes to great lengths to help build trust and accountability between potential guests and hosts through a variety of design elements (there’s even a TED talk from Joe Gebbia, co-founder of Airbnb on the subject).

The question is, what is the value of this peace of mind provided by Airbnb?

To answer this, take a second to think about a bad experience you’ve had with booking accommodation, be it a hotel or short-term/vacation rental…

How soon did your gut tell you that there was something wrong?

Our guess is that for most people, your mind was made up within the first 24-hours or less.

On a short stay of a few nights, you probably don’t mind a portion of your fees going towards peace of mind – say $40? But on an extended stay, how much are you prepared to pay on an ongoing basis once you’re satisfied with the quality of the product?

Airbnb’s service fee adds 10.6% to the cost of an extended stay, adding hundreds of dollars to the monthly rental cost. If you were going to book a place to live on Airbnb for a year, you could get six weeks free by booking directly with us, the operator. Our longest stay to date, by the way, is a whopping 282 nights. And our average extended stay guest spends nearly 70 nights with us.

The truth is, Airbnb has captured the market for extended stays because people don’t know where else to book a place for a few weeks or months. There is no dominant mid-term stay website that has the same brand recognition or reputation as Airbnb.

But why would you continue to keep paying Airbnb each month? Some people do, but many guests will prefer to book direct, particularly if the host is a professional operator that has the capability of processing direct bookings.

If Airbnb wants to capture 10% of the long-term rental market for real estate, what needs to happen to its pricing? The simple answer is that it needs to drastically reduce its service fees in accordance with the length of stay. The service fees for both the host and guest need to become so low that it’s not worth the low friction switching costs of booking direct.

What does that service fee burden look like? Well, if apartment landlords are willing to pay a locator one month’s rent and the average tenant stays two years, then that’s equivalent to 4.2%. And remember, the locator is probably spending a few hours accompanying you on various in-person visits, so their costs are far higher than Airbnb’s costs. I think therefore Airbnb needs to aim to get its service fee down to 3% or less for both the host and guest: a total of 6%.

There are a number of ways that it can achieve this, namely by reducing costs, increasing revenues through ancillary products, and by increasing the value of its product.

For example, Airbnb can reduce costs by encouraging a switch of ACH payments or charging a fee for credit card payments. It can earn a commission by offering supplementary insurance products for both parties, from renters’ insurance for guests to home insurance for hosts (they’d also love to see a squatter protection product). It can increase the value of its service by providing a positive rental history and contribute to the guest’s credit history – something potentially very important for international guests who don’t have a credit score and find it very difficult to lease a traditional apartment.

Essentially, Airbnb needs to take a wider perspective of ways to monetize its relationships with both guests and hosts, which we think will come by taking on more of a fintech mindset. And who knows, maybe it can even eliminate the service fee entirely!

While Airbnb has received its fair share of criticism from the hosting community (and is still viewed negatively by many in real estate circles), we are a big fan of the customers it brings to Lodgeur. We don’t mind paying the 3% host service fee, but it gives us a real knot in our stomachs when we see the fees that our extended stay guests pay them, especially those who chose to extend their stays for multiple months. Unfortunately, Airbnb’s terms of service prohibit us from soliciting their business directly, but hopefully, consumers will start to question the economics of booking through online travel agencies such as Airbnb and instead vote with their wallets by booking direct.

Lodgeur helps apartment operators boost their occupancy and NOI. We turn empty units into a flexible furnished product and manage them to attract a new type of customer.

Find out more about partnering with Lodgeur.